One of the key challenges for many blockchain projects is their ability to demonstrate non-trivial use cases outside of basic financial transactions. A major use case being explored by a number of blockchain platforms is the application of smart contracts in traditional supply chains.

A typical supply chain describes the organisational system that provides the means by which goods and/or services are procured from a supplier to a customer. Businesses usually will source a number of inputs from a wide variety of suppliers, taking those inputs and transforming them into their particular product before delivering that product to the customer.

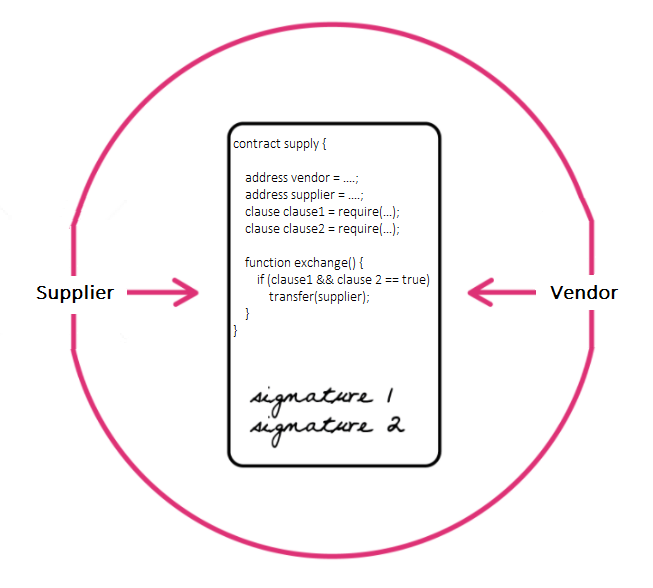

With businesses requiring security that their suppliers provide quality inputs to their production processes, traditional supply chain relationships are based on trust between the supplier and the producer that a quality standard is maintained. Whilst basic contracts can suffice in maintaining the integrity of some of these relationships, supply chains relationships can be greatly enhanced through the use of smart contracts.

Consider the following hypothetical scenario. A supermarket receives bread based on a traditional supplier contract it has with a bakery. Quality controls are defined as part of the contract, with remedies for breaches pursued in court. The major issue here is one of efficiency, the abstraction of the bakery’s supply chain makes it difficult for the supermarket to monitor the bakery’s processes. The relationship is based on trust that the supplier is producing the good the in the agreed way, and that appropriate quality control standards are implemented. In this case, the supermarket has to constantly check on the end product to verify the bakery is producing the bread in a way that is consistent with the paper contract.

Smart contracts are powerful here because of the ability to codify elements of the production process. Most major food suppliers have developed data-rich processes in supply chains, meaning much of the data required to implement smart contracts is already available. A smart contract allows vendors to codify clauses based on this data, providing far more flexibility in the management of breaches than a paper contract would otherwise be able to efficiently. Revisiting our hypothetical scenario, a smart contract in the supermarket/bakery context would give the supermarket the ability to ensure their purchased bread is produced in the way they require. Some examples of clauses could be as simple as tracking the temperature of the bread in transportation (to ensure freshness), or as complex as tracking the origin of the grains used in the production of bread. Currently there are a large number of blockchain projects built around the implementation of these supply chain smart contracts, such as the USD $780M Vechain, the USD $125M Walton Chain and the smaller Modium, Ambrosu and Origin Trail.

The current point of contention in the implementation of these contracts — and more widely in the use of the blockchain in supply chain processes — is the integrity of the data being used. The notion of a smart contract creating a ‘trustless’ exchange between two supply chain parties is challenged by the way in which a lot of production data is recorded. Many processes still require considerable human input for data recording purposes, with these providing a major point of vulnerability for data manipulation or error. In other words, until processes can be sufficiently automated to where there are no points of vulnerability (which you could also consider human interaction), these contracts have limitations in their security. Additionally, many companies do not want to share extensive data about their supply chain process, as it may compromise their competitive positions.

Because of these current limitations in supply chain security, the current crop of supply chain projects are heavily focused on providing traceable supply chain data to consumers (although with a view to expanding into B2B smart contracts in future). Origin Trail is a project based around the development of standardising supply chain data over the blockchain, but their major use case as right now is providing data to consumers about the production of food. Similarly, VeChain and WaltonChain have a number of partnerships based on the verification of product authenticity. Producers store data in smart contracts about their production inputs, providing data for consumers to view and evaluate when making decisions about products. Many of these projects also are not at a point yet where their blockchain platforms are ready to handle the data load of commercial supply chain deals, although this is not an issue limited to just supply chain platforms.

With smart contract platforms at such a nascent stage, supply chain contracts are more likely something that will be successful in the medium term rather than in the near future. The significant challenges related to the security of data in supply chains still need to be resolved independent of blockchain, and platforms must be able to handle the data load of commercial production without reaching bottlenecks. Once these issues can be overcome, supply chain smart contract adoption has the potential to be a huge driver of blockchain growth because of their potential for massive B2B revenue generation.

Check back next week for more.